By Rev. Canon Francis Omondi The future of our security; what do we do with Alshabaab?

Terrorism appears to be a puzzle we are unable to solve.

The viciousness, frequency and ease with which Al-Shabaab attacked Kenya has exposed the soft underbelly of our security organs in tackling terrorism.

Across the country and specifically the Northeastern and Coast Regions, there is an overwhelming sense that the security situation has changed. Not for the better.

Terrorism is never an accident. It is deliberate, calculated, systematic and precisely executed. It has to be to succeed. But it needs soil in which to grow. That soil is a community that is prepared, consciously or unconsciously, to permit it, collude with it. We are sitting on a powder keg!

The Chinese military philosopher Sun Tzu warned in The Art of War: “One who does not know the enemy but knows himself will sometimes be victorious, sometimes meet with defeat. One who knows neither the enemy nor himself will invariably be defeated in every engagement.” We appear not to either know our enemy or ourselves making victory over terror a mirage. There is an urgent need to distinguish who the real enemy is and a critical stock taking to understand ourselves and why we are in this war.

There is no doubt that the attacks by alshabaab indicated a clear understanding and exploited the trio pressure points of contemporary Kenya: ethnicity, land and corruption. Their intentions can be viewed from two fronts. To put pressure on the government’s continued deployment with AMISOM in southern Somalia by hitting targets that directly affect the financial interests of the middle “political” class and divide them externally and meanwhile insert cells and trained fighters into locations with pre-existing grievances and patterns of violence that the authorities have historically struggled to address and contain internally.

There are two recent research findings that I have found extremely instructive in understanding the challenges currently facing us: “Tangled ties: Al-Shabaab and the changing politics of violence in Kenya”, Published by the Institute for Development Studies,(Sussex University ) in collaboration with Centre for Human Rights and Policy Studies , by Jeremy Lind, Research Fellow, IDS and Patrick Mutahi, Researcher, CHRIPS] . And the International Crisis Group, Update briefing No. 102 of 25 September 2014 [Cedric Barnes, Horn of Africa Project Director, ICG].

The authors provided fresh analysis and ignored insights into the intersection of Al-shabaab with violence dynamics in Kenya and the politics. Of interest was their findings of the transnational actors and networks operation across the Kenyan-Somalia border and how they influence the politics and patterns of violence in Kenya.

Their scrutiny manifested ties connecting Kenya and Somalia in a wider, regional system of conflict.

While these researchers concur that reasons for the current increase in violence in Kenya are complex, their tracing it to the Government’s security responses is insightful. The Government’s central underlying logic in its war on terror has been to externalise the threat. Nothing seems to persuade the policy makers away from this premises and perception that Alshabaab is an external threat to peace and stability in Kenya. Thus a determination to guard and protect conflicts spilling over from Somalia.

There are however huge disruptions along this trail of thought.

The nature of terrorists we face:

We must come to terms with the fact that the war on terror has taken an ideological tone. In ideological war on terrorism, it is essential to understand the ideas one is at war with. This includes an understanding of how the Islamists perceive us.

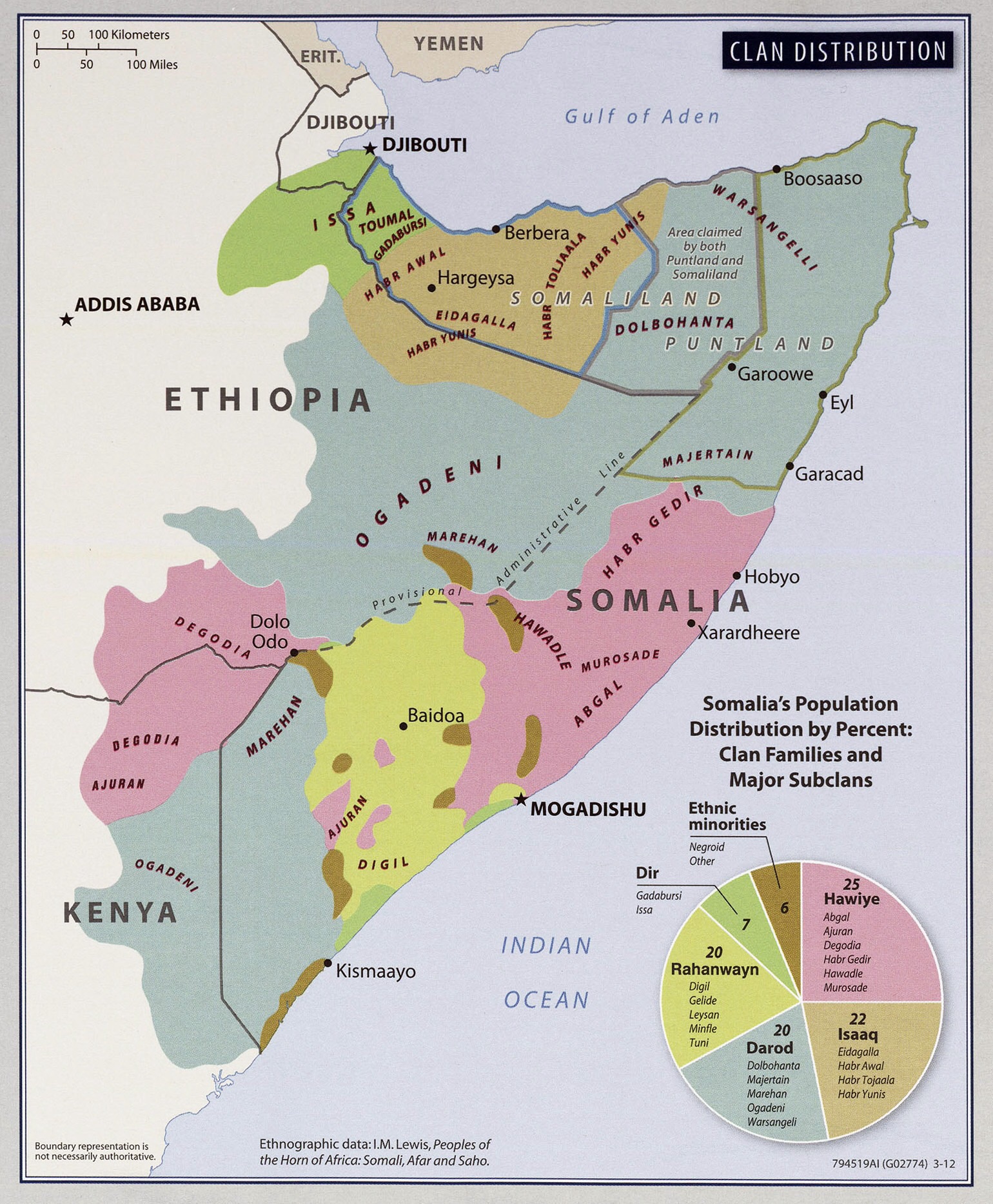

The civil war in Somalia had been primarily over the question of who controls which parts of the country (and the related resources, such as ports, junctions, and road-blocks) or even ‘the state’.

Only since 2006, as Markus Virgil Hoehne, of Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology, Halle/Saale, Germany argues “did the warfare in Somalia gain an ‘ideological’ quality pitting radical Islamists and their global networks against forces of an increasingly militant West and its allies.” What initially, in 2005, was a handful of unpopular hardcore militants had by 2009 become the dominant military force in southern and central Somalia. Most Somalis traditionally adhere to Sufism, the branch of radical Islam preached by Al Qaeda was genuinely unpopular among them.

They remained lukewarm when in 2006, the Union of Islamic Courts (UIC) unexpectedly took control of Mogadishu and much of southern and central Somalia. However the UIC was overthrown a few months later by an Ethiopian military intervention supported by some internal players and the U.S.

Between 2006 and 2009, these external interference intensified. Markus helpfully points that “the results of military intervention of Ethiopia and U.S. counter-terrorism swayed the public support for the radical ideology”.

In May 2008, Al Shabaab’s new leader openly pledged support for Osama Bin Laden. Consequently they took on strategies resembling those of Al Qaeda cells in other parts of the world: suicide bombings and remote-controlled explosives, beheadings of opponents. Foreign fighters and volunteers from the Somali diaspora including Kenyans have since joined the ranks of the movement.

The growing empowerment and resilience of Al shabaab:

Despite the pressures exerted and military gains on the Alshabaab, their conclusive defeat remains elusive. Like super bugs they have mutated. It was originally accepted our invasion of Somalia was not only to shield the country of terrorism but also to annihilate them. It has turned out to be a Long War. And this suits Al sahabaab.

The International Crisis Group Africa Briefing N°99, 26 June 2014, details how Al-shabaab’s armed units retreated to smaller, remote and rural enclaves, exploiting entrenched and ever-changing clan-based competition. Besides, one cannot help admiring the group’s proven ability to adapt, militarily and politically – flexibility that is assisted by its leadership’s freedom from direct accountability to any single constituency.

Again the same ICG policy briefing observed that the Alshabaab exploited “the advantage of at least three decades of Salafi-Wahhabi proselytisation (dawa) among Somali population; social conservatism is already strongly entrenched – including in Somaliland and among Somali minorities in neighbouring states – giving it deep reservoirs of fiscal and ideological support, even without the intimidation it routinely employs.”

From its first serious military setbacks in 2007 and again in 2011, Al shabaab has continually reframed the terms of engagement. It appears to be doing so again.

The consequence of our rushed and therefore counter-productive responses to terror:

Our lack of coherent strategy and clearly thought through responses has undermined our ability to win on terror. Crucial credible intelligence requisite to tackle war on terror, has been unavailable.

Prior to 2011, Kenyan security forces manning the border developed a kind of modus vivendi – albeit through local community peace networks – with Al-Shabaab militants as acknowledged by the ICG report.

But In February 2011, Al-Shabaab threatened to attack Kenya on the account of increased engagement in Somalia through the deployment of ‘Isiolo brigade’, a pro-Somalia government militia as early as 2009.

Abdirahaman Wandati, executive director of Muslim Consultative Council, in an interview insisted that,”they are still convinced that Al-Shabaab was not directly responsible for the spate of cross-border kidnappings that gave immediate justification for the October 2011 Kenyan intervention in Somalia, and that in fact they actively discouraged groups from carrying out kinetic activities in Kenya”. According to Muhiydin Roble, counter-terrorism researcher, the moratorium on attacking Kenyan interests was deliberate since it was a hub and gateway for foreign fighters, including diaspora Somalis; home to many sympathisers and financiers; and a place for medical care for injured combatants. Kenya also served as a major source of new recruits according to the “Report of the Monitoring Group on Somalia and Eritrea”, 20, June 2011.

Any de facto truce completely dissipated once the Kenya Defence Forces (KDF)’s “Operation Linda Nchi” (Protect the Country) got underway in October 2011. Since then apparently more attacks have been carried out in Kenya with the latest being the Garissa University Attack. Most experts agree that our military intervention in Somalia multiplied Al- Shabaab cells in Somalia, Kenya and the region. Al- shabaab were not destroyed in any of the intense battles that dislodged them from their abode. Most of their units simply vacated, carrying their weapons from towns and cities into the hinterland. New bases also were created to recruit and generate support for Al-shabaab in towns as far off in Nairobi, Mombasa, Kampala and several other rural towns. Kenya was now drawn into the internal war of control of Somalia.

Anti-Terror Policing Unit operations scared away crucial support from Muslims. “Tangled Ties ” [IDS university of Sussex] cites what human rights organisations have also documented cases of enforced disappearances, and mistreatment or harassment of terrorism suspects since 2007, in which they believe there is strong evidence of the involvement of the Anti-Terrorism Policing Unit (ATPU) (Open Society Foundations 2013; HRW 2014b). This has increased to alarming proportions in the coast and northern Kenya since the enactment of security bill Amendment act of 2014. ATPU is thought to be behind many of the extrajudicial actions (HRW 2014b).

Despite the ambiguities about who is behind the assassinations and abductions of Muslim leaders, the failure to hold anyone to account has deepened mistrust and tension between security agencies and Muslims.

The investigative capacity of the police is weak; the state has not been able to present strong cases that can withstand rigorous scrutiny in courts. This perhaps is one explanation that anti-terror officers are resorting to extrajudicial killings of suspects as the Open Society Foundations report of 2013: 47 alludes.

The emergence of new and unexpected players :

Al-Shabaab has kept its promise to bring the war to Kenya, whether by its own hand or local affiliates and by sowing divisions in a nation still not at ease with itself. Al shabaab cells are spread and scattered across the region and are no longer geographically confined to certain areas in Jubaland. They have active support and forces ready to heed their call from within the Kenyan boundary.

Though Al-Shabaab is identified as a Somali group, as a Salafi-jihadi organisation it does not recognise the modern nation-state boundaries, and usually appeals to the Muslim faithful rather than Somalis per se, as the ICG report explained. This includes Kenya’s 4.3 million Muslims – 11 per cent of the total population – who have been historically marginalised particularly in the northeast and coast regions.

The late Assistant Internal Security Minister Hon. Orwa Ojode, while launching operation Salama watch: security crackdown in Eastleigh in 2011 to flush out suspected Al-Shabaab members, remarked, “This is a big animal with its head in Eastleigh, Nairobi and its tail in Somalia.” He was right to think of danger with it. Its inexplicable why, with Hon. Ojode’s articulation, the security strategists were stuck in their long held position on the source of violent insecurity in Kenya to be Somalia and refugees. How could they ignore the shifting patterns of source of violence and emergent problem of Kenyan youth radicalisation?

The authors have shown us four ways of embracing these disruptions thus:

1. If we are to prevent a further deterioration of security and deny Al-Shabaab an ever greater foothold the Kenyan government, opposition parties and Muslim leadership should clearly acknowledge the distinct Al-Shabaab threat inside Kenya without conflating it with political opposition, other outlawed organisations or specific communities.

The patterns of violence in Kenya challenges the accuracy of the World Development Report (WDR) paradigm that separates and distinguishes between ‘internal’ and ‘external’ stresses as drivers of violence. The Tangled Ties (IDS University of Sussex), explained that it is the entwining of the two, and their interconnectedness through transnational actors and processes, that feeds into Kenya’s system of violence.

It is evident that before the latest episode of the conflicts, the economies of southern Somalia and Kenya were intricately bound through trades in livestock, other agricultural products, charcoal and household goods – with significant benefits of the trade accruing to Kenya-based wholesalers, retailers and transporters. From Somalia we have received the negative spillovers from Somalia’s conflict, and also benefitted greatly through an influx of Somali capital as well as the relocation of many of Somalia’s professional classes to Nairobi and other large Kenyan cities, as well.

Dr. Marcus Schultze-Kraft of IDS University of Sussex, UK in this study, “External Stresses and Violence Mitigation in Fragile Contexts: Setting the Stage for Policy Analysis”, IDS Evidence Report, N°36, convincingly clarifies that “the issue is not merely that internal and external stresses combine to generate stress but that they ‘actually relate to and reinforce one another, for they are interconnected through transnational actors and processes”.

2. There is urgent need to put further efforts into implementing and supporting the new county government structures and agencies, to start addressing local grassroots issues of socio- economic marginalisation.

Al-Shabaab has often exploited the deeply rooted disaffection amongst the peoples of the Kenya coast [in Mpeketoni] and north-east in gaining recruits to its banner. Anderson and McKnight (2014: 3) correctly observed that these affiliates may only see Al-Shabaab’s black standard as a temporary flag of convenience, but that may be enough to incubate and evolve an Al-Shabaab-led insurgency within Kenya.

Kenya’s security will only be strengthened by the pursuit of interrelated political, governance and security reforms addressing violence happening at the country’s margins and that have the greatest impacts for its marginalised populations.

The blueprint for addressing the threat of even worse insurgent violence at the margins lies in sincere implementation of the devolution provisions in Kenya’s 2010 Constitution. Not only are substantial public resources and decision- making powers devolved to county-level governments, but also the hope is that it will be easier to accommodate different interest groupings within a new governance and political- administrative architecture.

We must hurry to expedite the existing legal provisions to establish County Policing Authorities and County Peace Forums and provide institutional framework for counties to chart their own approaches to peace and security. Thus, following the moral intent of the 2010 Constitution to devolve powers and resources provides the greatest chance of finding a far-reaching and long-lasting solution to widening violence in Kenya.

3. We must carefully consider the impact of official operations such as Operation Usalama Watch, and paramilitary operations of the Anti-Terrorism Police Unit (ATPU) when they appear to target whole communities, and allow for transparent investigations and redress where operations are found to have exceeded rule of law/ constitutional rights and safeguards.

Spreading violence linked to the entwining of Al-Shabaab with internal discontent, and recent state responses to worsening security, show there is a pendulum swing between externalising threats to Kenya’s security and internalising the risk.

Kenya’s continued military involvement in southern Somaila has amplified the attachment to a logic of externalising the threat. This has been the mark of the state’s security responses failure. Tied to a lack of a clear goal when sending military personnel into Somalia in 2011, and making it an end in itself, has as ICG report No. 99 shown, not only undermined Kenya’s effectiveness domestically but also eroded the goodwill with Somalia’s government and its people. One will have to search hard to ascertain whether Kenya’s military involvement in Somalia is in the interest of Kenya’s security in the long run, more so for the alleged reason for intervening in the first place.

Withdrawing troops from Somalia may not necessarily lead to fewer attacks since Al-Shabaab has localised jihad within Kenya.

Further, the gains made recently in integrating Kenyan Somali into the country’s political society are threatened when there is politicisation of insecurity, and the scapegoating of Kenya’s Somalis and other Muslims who have also suffered greatly from Al-Shabaab’s violent attacks.

4. Harnessing the Muslim community’s involvement in addressing radicalization.

During the inter-religious public meeting in Garissa, just after the Garissa University attack, the Supreme Council of Kenyan Muslims vowed to come up with modalities to ensure all Islamic institutions come under one umbrella to stop radical madrassas that teach extreme ideologies without their knowledge and that of the government.

The long connection between Al-Shabaab’s current leadership and al-Qaeda is likely to strengthen. A critical breakthrough in the fight against the group cannot, therefore, be achieved by force of arms.

A more politically-focused approach is required that would allow for a dialogue within Islam to establish a faith that acknowledges contours of modern multi-religious society.

The SUPKEM offer made in Garissa needs a structured follow up. The government must facilitate Muslim-driven madrasa and mosque reforms, which should entail review and approval of the curriculum taught. Mosques vetting committees need to be strengthened in areas where they exist and put in place where they are absent.

Mounting evidence of enmeshing of ‘external’ and ‘internal’ stresses raises the need for more methodical and careful intelligence gathering. It also calls for a strategic rethink and different methods to address and mitigate violence simultaneously in Somalia and Kenya.

Externally, more military surges will do little to reduce the socio-political dysfunction that has allowed Al-Shabaab to thrive; in certain areas it may even serve to deepen its hold.

The latest combined African Union (AU) Mission to Somalia (AMISOM) and Somali National Army [SNA] offensive operation (“Eagle”) began on 5 March 2014. This offensive may certainly reduce the capacity of Al-Shabaab. But as sure as night follows day Al shabaab will hit back.

It’s not enough that KDF and AMISOM is in Somalia. Countering Al-Shabaab’s deep presence in south-central Somalia requires the kind of government – financially secure, with a common vision and coercive means – that is unlikely to materialise in the near term. The Somali Federal Government [SFG] has a deficit of political power and legitimacy and a surplus of international donor, mainly US, support. Turkey and the EU competition for influence has not worked in SFG’s favour.

SFG may gain credibility if it consider implementing, as outlined in the “National Stabilisation Strategy” (NSS), parallel national and local reconciliation processes at all levels of Somali society.

If TFG was an eight-year failure; it’s not rocket science to see what the SFG will be – another failure unless changes are instituted now.

With this it is important not to lose grip on internal drivers of violence.

There is a legitimate need to strengthen security, through supporting state security interventions, while carefully resisting the counter-productive targeting of Somalis and Muslims more generally, as well as security measures that impede a wider-reaching constitutional-based solution to worsening violence.

Will it be a tough ask imitating Al-Shabaab’s frequently successful techniques of facilitating local clan dialogue and reconciliation (as per the National Stabilisation Strategy, NSS), as well as religious education?

We must be quick at developing a new approach to establishing local and regional administrations that are authentically local and not props of outsiders.

Prioritise the making the local (Somali) political grievances that enable Al-Shabaab to remain and rebuild in Somalia the paramount focus, not regional or wider international priorities as recommended by the ICG briefing No. 99

The real question for Kenya is whether we have the vision and ability to reinvent our security – having embraced the scale of these disruptions.The skills, capabilities and organisational approaches that worked for delivering security in other context will not work for the complex war on terror.

This is the real challenge – a total transformation of our security approach. From operational-only to more relational skills. While optimising for efficiency we must go for optimising for opportunity and learning. From a culture of fear to one of acceptance and potential. While the five year plan should guide, we must work for an emergent strategy. From a focus on structure and roles to focus on process. While risk management is crucial we must include opportunity maximisation. From doing to being. From talking about the change we wish to see, to embodying it. From accountability to donors only, to accountability to those we serve living in poverty. From control by central government to empowerment. And so on…

From my perspective, very few have really understood the scale of change that is being demanded of us.

Canon Francis Omondi

All Saints Cathedral Diocese Nairobi.

Anglican Church of Kenya.

johnkingsleymartin

Hi Francis

Has this been used beyond your website?

John

waanglicana

Not yet john

p315

Well researched. You should consider having it published in the dailies

waanglicana

Thanks Jacob… si we were told dailies niza kufunga nyama! … I should appear in a journal by the end of month ….

Fr Enoch Opuka

This is detailed and incisive analysis. How I wish this could get to the decision makers.

waanglicana

Fr. Enock, I had shared this very article with some fellows up the ladder. It was the most prudent thing to do …one agree with Somalia parliament that voted Kenya to leave. We choose to occupy that things were improving….without the support of local Somalis it’s futile to hold on! We wanted peace for them through force….